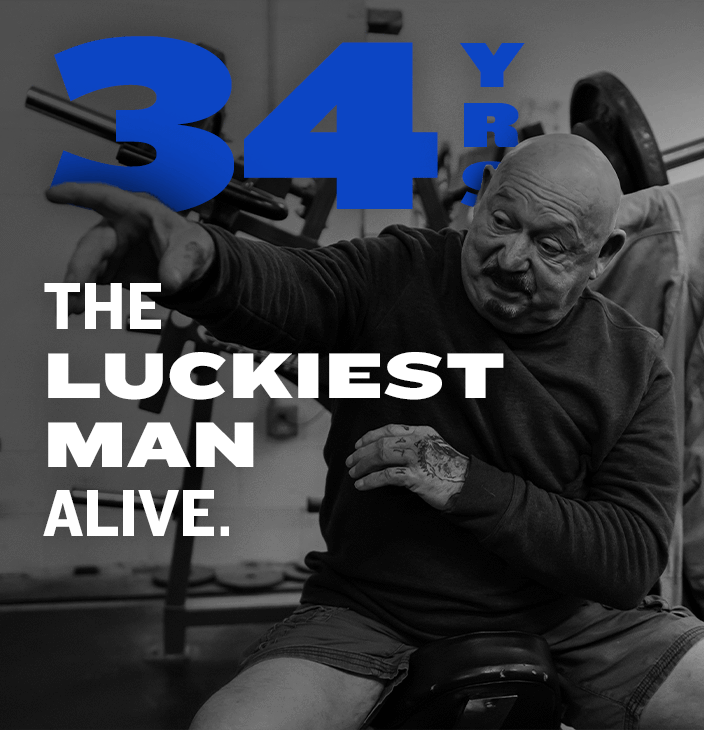

The Luckiest Man Alive

By Louie Simmons

Tags: Conjugate, Westside, Thoughts

Time to Read: 5min

It may sound like I am not lucky to hear my story, but it was a long journey to arrive where I am today.

When I was 10-years-old, I had very little in the way of money, but I found a job baling hay for a dollar an hour. One day, I had zero money to buy anything, and the next, I thought I was a millionaire. This feeling would last for only a short time, and then I would be back to being broke.

Two years would pass, and I was 12-years-old and at that age where I got into trouble. I couldn’t buy a break, and I was so broke. I had little drive to do anything, and I lived in the country with very few neighbors. Then, luck would step in when a family would move in down the street. The boys played baseball, and their Dad was a coach. His name was Mr. Gray. He was very enthusiastic, and it rubbed off on me. Now, I had a goal to be the best player on his team.

I was born to play baseball. I played one year in the Little League, and I hit 17 home runs to lead the city. I was a good player, really good, but there were lots of good ballplayers. One day we played a game in Valleyview, which ironically is only a mile from our Westside store today. It was the first field I had played that had a fence. I hit a home run over the fence. Usually, I would have to run around the bases to score, but this day I could trot around the bases and listen to the cheers for the first time. That home run forever changed my life. They were cheering for me, and I was someone special, or at least, I thought I was.

I also worked for Rathburn Construction doing manual labor as a block tender when I was 12. I would build scaffolding, carry blocks, and mix mortar for the masons. I would start one hour before anyone else and sometimes work late. It was bad luck for my ball playing, but good luck with making money and buying my own things.

'I learned that you had to find your own weaknesses and workouts.'

From then until I was 16, I saved enough money to buy a car. By 16, I had broken my ankle three times. Even at that young age, I had to recover from injuries.

I was not good at schoolwork. I could not concentrate on anything but girls, weights, and baseball. I was doing Olympic lifting until I was 18. Shortly after graduation, I had two experiences I remember well. One was good. I entered my first power meet in Dayton, Ohio. I finished 10th out of eleven competitors. Previously, I had always placed in the top in my Olympic lifting meets, but I beat only one 55-year-old man on that day. I was sold. I would never do Olympic lifting again.

The second experience was being drafted into the Army. After training, the Army planned to send me to Vietnam, but my Dad died. Since I was the sole surviving son of our family, the Army changed the plan. I lost my Dad, which was terrible luck, but it could have saved my life.

Luckily, while in Berlin, Germany, I found a magazine entitled Muscle Builder/Power. It had workouts by the Culver City, California, Westside Barbell Club. It became my first guide to lifting correctly. Boy, was I lucky! I now had Bill West, George Frenn, Pat Casey, and Joe DeMarco as my coaches, even though they had no idea who I was. The year was 1967, and my life was starting to improve.

The Army released me in 1969. When I returned to Columbus, I got my old job back, but I worked out of town for ten days, was home two days, and then back on the road. I had decided while in the Army that I was too short to try out for Major League Baseball. I now focused only on lifting.

I went into many gyms in the Midwest. I would see one strong guy in most gyms, and the rest would not be very strong. I noticed that just because one person found a program that worked, it did not necessarily work for the rest of the guys. I was lucky to see this, and I learned that you had to find your own weaknesses and workouts.

I also found you must sacrifice to be great. Nothing comes easy to get to the top. I started to compete in Ohio. I was lucky to lift with and compete against great lifters. It brought the best out of everyone. I competed against guys like Larry Pacifico, Vince Anello, Ed Matz, Roger Estep, and George Clark, to name a new. I set the Junior National Squat Record taking it from Tony Fratto, a good friend. In 1971, I made my first Top Ten lifts. Thanks to the Culver City boys and their articles, I made good progress.

Another article on the deadlift brought progress as well—Bill Starr’s “If You Want to Deadlift, Don’t Deadlift.” Like the original Westside boys, it called for rack pulls, box pulls, Goodmornings, power cleans, and small special exercises for a single muscle group. It worked, and I was lucky to have read Starr’s articles in muscular development. These articles would take my total from 1555 to 1655 in four months.

'it was good luck that KP made me mad enough to make a comeback.'

A book I read made a difference as well: Jonathan Livingston Seagull. I was changing my life in not just powerlifting, but in all aspects of life. One phrase changed everything: “Perfect speed is being there.” Thinking about this phrase made it possible to make a Top Ten lift for 34 years from 1971 to 2005.

After making a total that was 20 pounds more than what won the 1972 IPF, I knew what worked. I started to train right away and was doing Goodmornings at the Ohio State University Horseshoe Gym, which is at the end of the football stadium. While there, I lost my concentration and broke my L5-L3 and dislocated my sacrum with 435 pounds for five reps.

I ended up on and off crutches for ten months. Everything I had done in early training, I could no longer do. I had made a 630-pound squat, 390-pound bench, and a 670-pound deadlift with a two-hour weigh-in. Now, nothing. My luck had turned sour. I would be lucky again when I started doing an exercise that I would call the Reverse HyperTM. I also concentrated on my bench and made a 450-pound bench at 175-pounds bodyweight.

It took about two years to start training my lower back full speed, but it was going well. I pulled 700 pounds easy. By 1978, I was a Top 10 squatter, deadlifter, and I was fourth and fifth in the total in 1978-1979.

I had a small setback and could not train for two weeks, but the strongest meet that was not a national meet was the Bob Moon Memorial. I weighed 200 pounds and made an 1860 total—it was number nine in the 220-Class. And two weeks later made the 1890 total, and that total was number six, which was only 40 pounds off the 198-class total, but no one told me to go back to the 198-Class. Instead, I stayed in the 220-Class under 205 pounds.

In Nitro, West Virginia, at the YMCA Nationals, I made the third-highest total of 1950. But in 1970, Larry Pacifico told me I would have to build my bench up to a Top Ten lift if I wanted to win a national championship. He was right. Ten years later, I became eighth in the country and won my first nationals.

Six months before, at the IPF Senior Nationals, I had second place locked up with my opener of 672 pounds, but before I got the down signal, I tore my right bicep entirely off. Mike Lampert, the owner of Powerlifting USA Magazine, said that I was done with such a bad injury. But six months later, I made the third-highest 220-class total. Once again, my bad luck made me train twice as hard to win the Ys. Of course, I hurt my groin at the Ys and was down for some time.

'I also found you must sacrifice to be great.'

I had to work a lot from 1980 to 1990, and meanwhile, I had torn my patella tendon. In 1991, I completely tore off my patella tendon whole training for the 1991 Senior Nationals. The first thing I said to myself was, “How long will this take?”

I was back squatting 500 pounds in five months and 600 pounds in seven months. No mono lift; I had to walk the weight out. I got up to a 690-pound box squat, but I said, “I am 43 years old. What do I have to prove?”

My best squat was 821 pounds, and I had done everything but set a world record or win a world championship. Because of the injury, I would sit back as far as I could, so I just trained to stay strong.

Kenny Patterson has set lots of world records in the bench, but it was not going anywhere. To psyche him up, I said, “KP, I am going to come back and squat 700 pounds before you bench 700 again.”

KP said, “Old man, you will never have 700 pounds on your back again.”

At that point, I came out of retirement. KP would cause me to break my body into pieces, which was bad luck, but at the same time, I did things I would never have done without KP’s comment. I benched 600 pounds at 50-years-old before anyone else my age at the time could bench 550 pounds. I made a Top 10 lift at 57-years-old to achieve 34 years of making the Top Ten list.

I guess it was good luck that KP made me mad enough to make a comeback. Thanks, KP.

Because of my bad luck, I would help others by inventing machines and writing books to keep many people from having their own bad luck. My bad luck would also prove to be how I have been making a living with 13 US patents, 12 books, and a great staff led by Tom Barry, who entirely runs the business of Westside Barbell, leaving me to run the gym.

It seemed to be bad luck when I asked three all-time world record holders to leave the gym and had two quit at the same time. Still, now a rebuilding process has brought Westside new life with Jeremy Smith, Burly Hawk, and Eric Lewis on the men’s side and Sineaid Conley on the women’s side along with Kylie Goldsmith, our track star.

So, as you can see, I am again, the luckiest man alive.

Good luck, Louie